Encore un manuscrit du « Roman de la Rose » enluminé par le « Maître de Thomas de Maubeuge » …

Lot 62 de la vente Aguttes du 3 juillet 2008 (Neuilly)

Manuscrit enluminé sur vélin, premier quart du XIVe siècle, de 11 miniatures attribuées au Maître de Thomas de Maubeuge. 136 f. non numérotés, complet avec 17 cahiers de 8 f. 175 x 250 (125 x 185) mm, réclames en fin de cahiers, copié à l’encre brune par une seule main. 2 colonnes de 40 lignes. Réglé à la pointe sèche. Nombreuses lettrines filigranées peintes en rouge ou bleu, avec filigranes de ton opposé bleu-vert ou rouge, rubriques en rouge [la première rubrique au f. 5 : Ci parole oiseuse], une initiale de 8 lignes de hauteur (f. 27) ouvrant le texte de Jean de Meung, d’or sur fond bleu avec un champ rose foncé agrémenté de motifs dorés. Couvrure d’attente en vue de recevoir une reliure jamais réalisée (avec cahiers reliés et couverts de parchemins notariés du XVIIIe siècle portant des timbres de la Généralité d’Orléans).

Texte f. 1-27, Guillaume de Lorris. Incipit: Maintes genz dient que en songes // N’a se fables non et mençonges… Explicit: […] Que je n’ai mes aillors fiance (v. 1-4028) ; f. 27-136, Jean de Meung, rubrique, Ci comence mestre Jehan de Meun; incipit : Et si l’ai ge perdue espoir…Explicit: […] A tant fu jor et je m’esveille. Explicit li roman de la rose (v. 4029-21750)

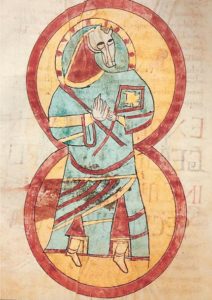

Décoration Manuscrit illustré de 11 miniatures : f. 1 : L’Amant endormi, surmonté d’un décor de rose, est visité par Danger qui porte un bâton. Cette image débute tous les Romans de la rose du XIVe siècle, dont ceux du Maître de Thomas de Maubeuge. Miniature en frontispice ; initiale ornée avec prolongement de baguettes ; scène de poursuite d’un lièvre par une hermine ; f. 1v : Haine et l’Amant ; f. 2 : (1) Amant avec Vilainie et Felonie qui lui donne une coupe ; (2) Convoitise et l’Amant ; (3) Avarice et l’Amant ; f. 2v : Envie et l’Amant ; f. 3, (1) Tristesse et l’Amant ; (2) Vieillesse et l’Amant ; f. 3v : L’Amant avec Papelardie ; f. 4 : L’Amant et Pauvreté vêtu de blanc tenant un bâton ; f. 27: L’auteur Jean de Meung à son pupitre visité par l’Amant.

Le Maître de Thomas de Maubeuge se reconnaît aux grands yeux angulaires, les lèvres et les joues rehaussées de rouge, les cheveux élégamment bouclés sur le front. Ce Maître a peint cinq Romans de la Rose : Frankfurt Stadt-und-Universitatsbibliothekek lat Qu 65 ; Paris, Bibl. de l’Arsenal ms. 3338, Paris, BnF. fr 1559 ; 9345 ; 12589. Cet artiste est connu sous le nom de Maître de Thomas de Maubeuge d’après le libraire parisien Thomas de Maubeuge mentionné pour la première fois en 1343. Il travaille en 1313 pour la comtesse Mahaut d’Artois qui lui commande une Bible en français et une Vie de saint. Il est mentionné jusqu’en 1349. Ce libraire emploie régulièrement pour les commandes de prestiges deux enlumineurs, à savoir le Maître de Fauvel et le Maître de Thomas de Maubeuge. Il a peint plusieurs manuscrits dont un code de Justinien pour le roi Charles V en 1342 (S. Cassagnes Brouquet, L’image du monde un trésor enluminé de la Bibliothèque de Rennes, Rennes, 2003).

De même, voir Rouse & Rouse, Manuscripts and their makers, tome II, appendix 7F: Manuscripts illuminated by the Master of Thomas de Maubeuge, p. 176-179.

Provenance : 1. Marque de possesseur (fin XVe ou début XVIe s.) inscrite à l’encre au recto du f. 136 et formulée à deux reprises. Encre très pâle, presque invisible : Ce livre est a Pierre Chevrier, seigneur de Ville[neuve]; C’est a P. Chevrier, seigneur de Javanrennes. La famille Chevrier est une famille de la région d’Issoudun, seigneurs de Villeneuve, Breuil-de-Beauvilliers et de Javanrennes. Il semble que Pierre Chevrier ait épousé Catherine Le Roy, fille de André Le Roy, Seigneur de Villeneuve-sur-Cher. Le fils de Pierre Chevrier était André Chevrier, seigneur de Villeneuve, de Janvarennes et Billeron, qui se maria en 1503 (voir G. Thaumas de la Thaumassière, Histoire de Berry, Bourges, 1868, vol. III, p. 84-85 : Seigneurie de Villeneuve). – 2. Propriété en 1887 du Maire de Villeneuve [Villeneuve-sur-Cher ?]. Lettre adressée à M. le Maire de Villeneuve, datée St-Florent [-sur-Cher ?] le 19 octobre 1887 et signée V. Mourié. Ce dernier décrit son exemplaire lacunaire du Roman de la Rose et demande à M. le Maire de Villeneuve (dont le patronyme n’est pas précisé) l’autorisation de photographier le présent exemplaire en sa possession, bien complet du texte.

Source

Catalogue de la vente Aguttes, avec 2 photos. En ligne sur le site Bibliorare [Lien]

Voir d’autres pages [Lien]

La Légende dorée ~ The Golden Legend …

Sur le site EBAY, un exemplaire de la Légende dorée …

Voragine, Jacobus de. Dat Duytsche Passionail. Dat eyrste deil [The Golden Legend] [Legenda Aurea]. Cologne: Ludwig von Renchen, 1485.

Part One (of two parts). Folio (285 x 215 mm.). Ff. 252 (lacking ff. 71, 78, 79, 125 and last blank). Gothic letter, double column, three large woodcut initials, initial spaces with guide letters completed with green and red painted initials, large woodcut border on ff. II, in four pieces, of vines with flowers, fruit, birds and man to lower outer corner, 97 woodcuts with repeats, illustrating each legend, one half page woodcut, all in strictly CONTEMPORARY HAND COLOURING, (yellows, browns, green and reds), a line of blind printing to lower half of title page.

Contemporary marginalia by each woodcut, large painted armorial device on title page, (depicted hanging from a nail) with motto “Verstaet, Eerghy, Oordeeld” in a scroll above with initials HH to sides and monogram at centre (as yet unidentified).

Title page, ff. II and last ll. a little dusty and a little chipped at fore-edge, paper label removed from verso of title-page with traces of old repair at inner margin recto and on verso of last ll., lower outer corner of these three leaves also with ancient restoration, occasional thumbs marks and minor soiling to margins, a few small marginal tears with ancient repairs not touching text.

A rare copy of one of the few illustrated incunable editions of Jacobus de Voragine’s Legenda Aurea, or Golden Legend – not be confused with Der Heiligen Leben, or other legendaries of the period. An excellent example, with superb contemporary hand colouring of the woodcuts, in an unusual Low German translation. The printer, Ludwig von Renchen, published a Latin edition simultaneously, without the woodcuts (BMC I 267); he clearly designed this illustrated edition to reach a much wider audience.

A tradition emerged at an early stage in Germany of dividing Legendariesin to two parts: sometimes referred to as \ »Winterteil\ » and \ »Sommerteil\ », or \ »Winter\ » and \ »Summer\ » parts. This tradition continued into the printed era, and the two parts of incunable German Legendaries were often printed up to a year apart.

Renchen applied this tradition (in addition to the traditions of illustration and use of the vernacular found in other German incunable legendaries) to his edition of The Golden Legend of 1485: Part One was published on 21 July; Part Two on 31 October. The two parts of German incunable legendaries are now almost invariably encountered separately (see our summary of auction records below).

The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine is a collection of fanciful hagiographies, lives of the saints, that became a late medieval bestseller. It was probably compiled around 1260, initially titled simply Legenda Sanctorum, or \ »Saints’ readings\ ». More than a thousand manuscript copies of the work survive, and printed editions appeared quickly, not only in Latin, but also in every major European language. It was one of the first books William Caxton printed in English translation; his version appeared in 1483. It remains a treasure-house of European culture, crammed full of the things which everyone, once upon a time, used to know, and is the closest thing we have to an encyclopedia of the lore of the saints in the late Middle Ages. As such it is invaluable to art historians and medievalists who seek to identify saints depicted in art by their deeds and attributes.

The textual history of the Golden Legend in Germany is complex. In the medieval period, elements of the Golden Legend were incorporated into a number of other works, most famously the Vers-Passional, completed between 1290-1300, and Der Heiligen Leben, complete between 1396-1410. Der Heiligen Leben was composed by a Dominican friar from Nuremburg, and contains 251 legends from multiple sources including the Vers-Passional, the Martyrbuch, The Golden Legend, the Speculum Historiale of Vincent of Beauvais, and the Latin Vitae Patrum – only 31 of the lives recorded are drawn from the Golden Legend (see Jeep, p. 445). As a work that often appeared in the vernacular, and that was aimed at a wide audience, editions of Der Heiligen Leben had a strong tradition of illustration, in contrast to The Golden Legend. At least 14 of the 23 incunable editions of Der Heiligen Leben were illustrated with woodcuts. In contrast, only about 20 of the 152 incunable editions of The Golden Legend were illustrated with woodcuts – most of these being French and German vernacular editions.

For reasons of tradition and convenience, bibliographies (most notably the ISTC), auction records and libraries often catalogue Der Heiligen Leben as authored by Voragine – concealing the fact that The Golden Legend and Der Heiligen Leben are in fact entirely separate works.

It should be noted that the present copy of Renchen’s 1485 Low German Duytsche Passionail is not Der Heiligen Leben – it is a translation of Voragine’s Golden Legend (see Kalinke, p. 7). We have been unable to establish which stemma of the Golden Legend Renchen used (and whether he relied on printed or manuscript sources), but his edition includes 159 of the 180 Lives or legends included in the critical edition prepared by Graesse in 1845 (the only modern critical edition in Latin), the vast majority in precisely the same ordering. Interestingly, Renchen includes an appendix after the main body of the text with a number of additional legends of local and north European interest (in common with Caxton, who also included additional lives of English interest in his translation).

The woodcuts in this edition emphasize line and pattern over three-dimensional form; there is no cross hatching or attempt at perspective and as such they represent a much earlier style of illustration derived from the first professional wood-engravers who were originally card-makers. (Wood-engravers were generally called card-painters – Briefmalers – in Germany, from about the middle of the fifteenth century).

The painting in this copy has remained remarkably fresh and vibrant (exposed to sunlight the fragile pigments often fade and discolour). Coloured copies are significantly rarer than ordinary copies. As popular and very well used works, they were often read to oblivion or mutilated in the religious wars of the next five centuries, and are rarely complete or in good condition. Of the 26 copies in ISTC 16 are imperfect. A lovely example of this wonderful piece of late medieval popular art.

Hand-coloured, illustrated incunable Golden Legends are rare on the market – and are usually found incomplete. Of uncoloured, illustrated incunable Golden Legends, APBC lists 4 copies, 3 of these incomplete.

Of hand-coloured, illustrated incunable copies of Der Heiligen Leben, (see above for the relationship between the Golden Legend and Der Heiligen Leben), ABPC lists 8 copies sold at auction worldwide since 1975 (one of these copies selling 3 times). All of these copies are Sommerteil or Winterteil only (6 copies of Sommerteil, 2 copies of Winterteil). The most recent hand-coloured and illustrated incunable copies of Der Heiligen Leben sold at auction on 24/10/07 (Bloomsbury Auctions New York, lot 13: Urach, 1481, Sommerteil only, lacking one leaf, $96,000), and on 28/10/2005 (Pierre Berge Auctions, lot 5: Augsburg, 1471, Winterteil only, Euros €210,000).

SOURCE : Nicholas Marlowe Rare Books

http://stores.ebay.fr/Nicholas-Marlowe-Rare-Books

Auction: vente Châteaudun du 25 mai 2008

Lot 6: Livre d’heures, début XVe, 3 f. seulement.

Lot 7: Livre d’Heures, XVe s. Pas de description.

Catalogue sur Interenchères avec qq photos

[Lien]

Auction Bloomsbury (mars 2008) : \ »Exemplari\ », \ »trattato dell’ abbaco\ », Livre d’ heures …

Bloomsbury Auctions, Inc., New York présente à la vente (sur Ebay) plusieurs précieux manuscrits, dont un exemplari, origine France, copié par un Karolus. Il s’agit peut-être de Charles, copiste cité par R. H. Rouse & M. A. Rouse, Manuscripts and their makers, II, p. 21, comme étant censitaire en 1285 de Saint-Merri. J’ai moi-même lu ce nom dans le Paris AN S 1626/1 qui est un censier de l’abbaye Sainte-Geneviève, daté de 1276: Karolus scriptor (in bordellis)

Les exemplaria servaient de modèle aux copistes et étaient loués pièce par pièce.

Descriptions d’après notices en ligne

[Lot 3B] ARISTOTLE. [Organon.] Composite manuscript on vellum, containing: PORPHYRY. Isagoge; ARISTOTLE. Categoriae, Liber peri hermenias [De interpretatione]; BOETHIUS, Anicius Manlius Severinus. Liber de divisione, De differentiis topicis; ARISTOTLE. Liber topicorum, De sophisticis elenchi, Priora analytica, Posterioria analytica, in Latin. France: mid- and late 12th century and early 13th century]. Decorated manuscript on vellum. 173 ff., complete. Collation: 114 2-68; 7-108 116 125 (of 6, f. 12/1 blank removed); 13-146 158; 16-198; 20-228. Detailed contents: Porphyry, Isagoge ff.1-4 and 11-14v (ff. 5-10v a second copy inserted in the middle of the first gathering); Aristotle, Categoriae ff. 14v-25v; Aristotle, Liber Peri hermenias ff. 25v-31v; Boethius, Liber de divisione ff. 31v-38v; Boethius, De differentiis topicis, books I-III, ff. 38v-53v; Boethius, De syllogismus categoricis, opening sections only, ff. 53v-54v; Aristotle, Liber topicorum ff. 55-97 [a blank leaf, the pair to ff.55, has been removed from the end of this section but there is no gap in either this text or the following]; Aristotle, De sophisticis elenchis ff. 98-117v; Aristotle, Priora analytica, in the Chartres recension ff. 118-149v; Aristotle, Posteriora analytica ff. 150-172v; notes on humors and brief quotations, additions in a 15th-century hand, ff.172v-173v. Six discrete text blocks (200 x 135 mm. and smaller), each ruled in a different pattern of between 29 and 38 lines, written in dark brown or black ink in different small proto-gothic or gothic bookhands. Opening initials of pale red or brown and red, diagrams in text on ff.132v and 138 and in margin of f.3, extensive marginalia in various hands, ranging from detailed explanatory text and diagrams to informal marginal sketches. Modern blindstamped calf over 15th-century bevelled wooden boards, 15th-century French manuscript deed on vellum (written on recto of a folded folio leaf), formerly used as pastedown, at end. Condition: a few wormholes in first leaves, rubbed or stained with some loss to text of ff. 1 and 2, f.106 with repair crossing text, vellum repairs to lower corner of f. 11, outer margin of f. 74 and lower margin of f. 91. Provenance: The individual text blocks are all in French hands, and several of the annotations are in French, providing evidence that the collected manuscript remained in France. Many of the marginalia are seim-effaced A few are dated to the mid-13th century (1240 and 1269). Some of the annotations are unrelated to the text, transcribing for example, the opening of a letter, or recording the receipt of a mattress, but one note, on f. 117v, records payment to a scribe and may relate to the manuscript’s production (Mag[ist]ri karoli scriptoris p[ro] exemplari. ii sol[idi]) (1). — The manuscript deed that was used as a pastedown, dated 1407 and relating to a marriage settlement of Johanette, daughter of Jehan, living at \ »Poulorgny,\ » suggests that the manuscript was still in France when it was rebound in the fifteenth century. — Count Oswald Seilern (1901-1967, booklabel, sale Christies London, 26 March 2003, lot 3). A remarkable composite manuscript, consisting of a compendium of discretely produced manuscripts, originally from more than one codex, that were assembled in the 13th century to provide the entire corpus of works that make up the Aristotelian Organon (\ »The Instrument\ »). Organon was the name given by his followers to Aristotle’s six works on philosophical logic, accompanied by Porphyry’s introduction (Isagoge) and the commentaries by Boethius, through whose Latin translation the works were rediscovered and disseminated throughout medieval Europe. This corpus became the basis for the study of logic and the determining influence on scholastic thought. the assemblage of all of these texts in this thirteenth-century volume provides valuable evidence of the revival of interest in and circulation of the fundamental texts of Antiquity during the in the 12th and 13th centuries. The composite nature of the manuscript mirrors the incremental rediscovery of the Aristotelian corpus during the \ »Renaissance of the twelfth century\ »: the first section contains the works subsequently known as the logica vetus, written in a particularly fine and elegant hand, apparently in southern France in the middle of the 12th century. The quality of the penmanship in this section may have been the inspired the addition of the other texts and possibly ensured the preservation of the volume as a whole. The remaining texts contain the other logical texts of Aristotle, which became known as the logica nova, as they were only recovered in the course of the 12th century. It is not clear whether these other texts were added in a single campaign at a later date, although this seems unlikely, but it is evident that some attempt was made to give them a more uniform look by the addition of the pink-red initials and occasional paragraph marks. The annotations and marginalia attest to the manuscript’s extensive use by various readers from the 13th century and later. Precise clues as to provenance are scarce, most names being illegible or incomplete. The notes include erudite explanatory text and logical diagrams, including one, in a 13th-century hand, which schematically depicts Porphyry’s questions on the status of \ »universals\ » (the problem that brought forth scholasticism), as well as frivolous sketches: at the foot of f.51v is a labeled sketch of a physician holding a urine bottle, and in the outer margin of f.109 a knight astride his horse. Medieval Aristotle manuscripts of this quality and early date appear rarely on the market.

Lot 16b: North Italy, Lombardy?: early 16th century

An abbacus manuscript, in Italian. Decorated manuscript on vellum. [Italy], 1419. Signed and dated by the scribe, Joh[ann]es de Strasburg, 18 April 1419. 47 leaves: [19 2-48 56 68]. Possibly incomplete at beginning. Written in brown ink in a small upright cursive, single column, up to 51 lines (variable), section headings and paragraph marks in red, marginal initial capitals and table headings with red capital strokes. Catchwords in center of lower margins on final versos. Ten pages with geometrical diagrams (circles and triangles). Signed and dated at end \ »facto e chompiuto adi 18 April 1419 / [in red] Qui scripsit scribat et sember cu[m] d[o]m[i]ni vivat / Amen solamen Steyg der blin uff den lamen / Joh[ann]es de Strasburg\ ». Modern black goatskin. Condition: First leaf wrinkled and with large stain obscuring one to two words each from 7 lines on recto, occasional small stains Provenance: \ »Piero (?)Strozzo,\ » contemporary ownership inscription at end (of a member of the Florentine banking family?); several illegible or partly eradicated early inscriptions on final verso. — Later manuscript notes with geometrical diagrams on 5 leaves at end. a very fine example of a \ »trattato dell’ abbaco\ » or italian pedagogic manual of commercial mathematics, accounting and geometry. Beginning in the thirteenth century the rise of international trade and banking companies in the Italian city-states prompted the formation of vernacular schools in which commercial mathematics, accounting and writing were taught to sons of the merchant class. This was a radical departure from the humanist educational curriculum, which, if it included mathematics at all, was limited to classical or medieval Latin mathematics – algorisms for determining moveable feast days in the church calendar, or Euclidean geometry. Known as abbaco, this practical course of mathematics was recorded and transmitted in manuscript books, of which several hundred are known to survive, all in Italian, and the vast majority in institutional collections. Long thought to be abbreviated vernacular versions of the Latin Liber abbaci of the 13th-century mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci, an encyclopaedia of practical mathematics, these abbaco manuscripts, of which the earliest dated example is from 1290, may in fact derive from a more widespread culture of commercial mathematics, already known by Fibonacci, and probably flourishing in Provence and/or Catalonia before reaching Italy. From the fourteenth to the sixteenth century so-called abbaco schools flourished throughout northern Italy, in different forms, with the Florentine version being a separate two-year course of study administered to boys aged 11 to 14, while other towns integrated the abbaco teaching into the vernacular schools. The present manuscript opens with problems of addition, multiplication, and division, including fractions. (\ »Abbaco books. did not usually explain addition and subtraction, probably leaving this to the teacher to do\ » – Grendler, p. 313). It proceeds quickly to \ »the heart of abbaco. solving the mathematical problems of business. The ordinary abbaco book might contain four hundred problems and their solutions, of which the largest group by far were business problems (op. cit., p. 314). This manuscript is no exception. The many problems, most presented in a literary, story-telling form that is typical of the genre, relate to commercial arrangements, payment of merchandise, commercial partnerships, measurements and weights, money exchange, etc. Several schematic tables show how to calculate distances; others show different accounting methods or methods of calculating interest. A few other problems are of the \ »recreational\ » sort described by Grendler, designed to exercise purely mathematical skills. The final section, illustrated with neat diagrams, is devoted to practical geometry. Like all abbaco manuscripts, this one contains a trove of information on late medieval Italian commercial practices. The fact that the manuscript is signed and dated adds to its interest and documentary value. The concluding jingle of the scribe Johann from Strassburg is written in an unusual mixture of Italian and German. Written in the lower margins in a seventeenth- or eighteenth-century Italian hand, the later notes testify to the manuscript’s continued use two or three centuries after its production. Abbaco manuscripts appear very rarely on the market. Cf. Paul F. Grendler, Schooling in Renaissance Italy (Baltimore & London 1989), chapter 11, \ »Learning Merchant Skills\ »; Warren Van Egmond, Practical Mathematics in the Italian Renaissance: a Catalog of Italian Abbacus Manuscripts and Printed Books to 1600 (Florence 1981). Cf. Paul F. Grendler, Schooling in Renaissance Italy (Baltimore & London 1989), chapter 11, \ »Learning Merchant Skills\ »; Warren Van Egmond, Practical Mathematics in the Italian Renaissance: a Catalog of Italian Abbacus Manuscripts and Printed Books to 1600 (Florence 1981).

ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPT LEAVES , France,15th Century. Three leaves from a noted Missal , in Latin, on vellum. [France, ? Britanny, c. 1430s]. each (310 x 230 mm). Double column, 30 lines in black ink in an upright gothic bookhand between 4 verticals and 31 horizontals ruled in grey, one leaf with respectively 9 and 10 lines of musical notation on verso, in square neumes on four-line red staves. Rubricated in red, one heading in gold. Guide letters for rubrics in margins. Numerous illuminated initials in various sizes: three large initials in blue or red on burnished gold grounds with red or blue infill and white penwork decoration, 43 three- to one-line initials in gold on blue and red grounds and with gold, blue and red foliate infill, three line-fillers or Greek crosses in blue or red on gold grounds. Three pages including the page with music with bar borders in burnished gold and pink or blue and with full illuminated borders of acanthus leaves and flowering naturalistic plants in red, blue, green, or gold and hairline tendrils in black ink terminating in gold disks, flower buds and trefoils. Condition: a few small marginal holes and some holes in text block caused by acidic ink. Provenance: Cornelius J Hauck Collection, sale Christies New York, 27th June 2006 lot 104. These leaves were part of a lavishly decorated Missal. The style of the border decoration, particularly the use of orange and liquid gold fruits, evokes the illuminator known as the Master of Margaret of Orléans (duchess of Brittany), and the manuscript may have been produced in Brittany. The leaves contain the opening of the Introit Benedicta sit sancta trinita for Mass on Trinity Sunday, the Introit Resurrexi et adhuc tecum for Mass on Easter Sunday, and the Preface Per omnia secula seculorum from the Canon of the Mass.

BOOK OF HOURS, use of Rouen, in Latin. Late 15th Century Northern France (probably Rouen), [c. 1470-80 and c. 1520]. Illuminated manuscript on vellum. Small 4to (160 x 110 mm). 236 leaves, 1 blank, complete, red ink foliation skips a leaf between fols.86 and 87, ruled in red ink, 25 lines, written-space 112mm. by 70mm.

Bloomsbury Auctions

Site web [Link]

PAGES ANNEXES

Auteur du blog : Jean-Luc DEUFFIC